Memes and Madhabs

Like many young Muslims in the diaspora, my community in Cardiff, Wales was diverse. Muslims have a long history in Wales, but larger flows of migration initially began with seamen from Somalia and Yemen settling in Tiger Bay, followed by migration from South Asia to address labour shortages in the late 20th century.

This also meant being exposed to a great deal of diversity in how Islam is practiced. Of course, there is remarkable continuity, and the untrained eye might not detect the often-subtle differences, but when I first went to a Hanafi masjid I definitely noticed.

As the imam drew closer to the end of Surah Fatiha, I took a deep breath and enthusiastically let out a mighty “Ameen!”. This was one of my favorite parts of praying growing up as a kid. But with the exception of the odd grunt, the silence was deafening.

“Sugar”, I thought as I started to sweat embarrassed by what just happened. The kid next to me whispered “what are you doing?”. Some of us used to chat about cartoons and other pressing issues during prayer as kids, so asking that question didn’t seem like such a big deal at the time.

I’m Somali, and though my family didn’t teach me much about madhabs (schools of jurisprudence) we followed the Shafi’i one. “Dad, they did it wrong” I told my father, puzzled by the experience. He explained to me that evening that people do things differently depending on where they’re from, and that Sunni Islam has four major madhabs.

“It’s not a big deal” he gently reminded me, but that’s why they don’t connect their feet, hold their hands lower and take part in collective supplication after prayer.

The word ‘madhab’ loosely translates as “to go”, or “to take as a way”. Each school of jurisprudence contains a particular set of interpretative possibilities and internal variance in accordance with slightly differing principles and methods to derive religious rulings which touch on almost every aspect of a Muslims life from marriage, to eating food.

Context also had a big influence as the different schools of law matured at differing periods in Islamic history, and developed their bodies of law in very different spaces and times.

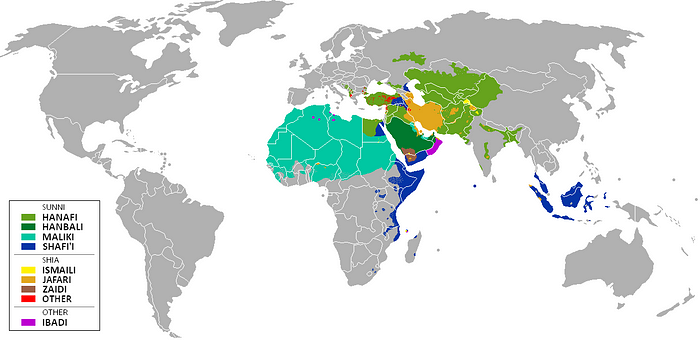

The Maliki school of law for example emerged in Madinah and is the oldest, whereas the Hanafi school of law (which has the largest following) developed in the more cosmopolitan Fertile Crescent in Iraq where Muslims were a minority and is widely practiced on the arc between Bosnia and Bangladesh (with the exception of Shia majority Iran and parts of Iraq, which follow the Ja’fari school of jurisprudence).

“Early Sunni Islam, back when authority was vested in the Quran, and the example of the Prophet, was, nonetheless confronted with an enormous body of Prophetic narrations or hadiths”, says Haroon Sidat, a graduate from an Islamic seminary who is also currently completing a PhD on British madrassas at Cardiff University.

These narrations he said had been scattered all over the Islamic world in various forms, some of which were even fabricated. This made it difficult to discern how Muslims should behave, what was normative, what was not and how to worship.

“Much of the science of Islamic jurisprudence was developed in order to provide consistent mechanisms for resolving such conflicts in a way which ensured fidelity to the basic ethos of Islam.”

“This is where the madhabs come in. Though we had a number of madhabs that emerged, the Sunni Muslim community settled with the Four Imams: Abu Hanifa, Malik ibn Anas, al-Shafi’i and Ibn Hanbal” Haroon continues. “They act as safeguards to protect Muslims from misinterpreting scripture.”

I’d eventually end up going to a Pakistani madrassa to study Quran, and began to understand how the Hanafi madhab works, what to do and what not to, which has enriched my understanding of Islam.

But madhabs go further than those relatively minor differences and a renewed interest has emerged online through a series of satirical memes in the Muslim Twitter-sphere.

The memes started a few weeks back by Zain Siddiqi, a young Muslim from Phoenix, Arizona.

“It began as a bit of fun” he told me. “I really enjoy making memes, but I also enjoy studying Islamic law and different aspects of the religion.”

“Initially I just thought I would tweet one out and it would get 10 likes or something, and I would just go back to making mundane political commentary on whatever was happening” he continues. “But all of a sudden people were saying how much they enjoyed them and how much they were learning from them.”

The most popular one, which played on the silence of Muslims who practice according to the Hanafi rite during prayer has been liked over 700 times, and retweeted over 200.

Zain is currently a student of Political Science at Arizona State University, where he also works closely with his Muslim Students Association (MSA) and is a blogger for Traversing Tradition. The community he grew up with was largely Arab with a few people of Somali ancestry.

Of Indian heritage, he says he’s a “staunch Hanafi” which is why so many of his memes are about the Hanafi madhab, but much like me, he says the cosmopolitan space he grew up in had its impact on him.

“I’ve had Quran teachers who have been Shafi’i or Hanbali. Some of my best friends are Somali and they tend to be Shafi’i. So, growing up we had different rulings with different authority figures telling you to do things” he says.

“It was confusing at times because you’d often hear conflicting reports about what to do or what to believe.”

One of his memes alludes to some of the potential complications. Sunni Muslims pray five times a day in usual conditions, but three out of four madhabs permit believers to combine prayers when travelling to reduce the difficulty of the journey.

For followers of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence who have their highest concentration in South Asia, this doesn’t apply which inspired this meme.

“In the last decade and a half”, says Dr Sadek Hamid, who studies Muslim youth culture in West and has authored many books on the subject, “Western Muslims in the UK, Europe and the US who identify with their faith have engaged in a process of religio-cultural hybridization.”

“They are crafting new Muslim youth subcultures in the arts, music, media and fashion by synthesizing their religious values with a western flavor.”

His research has shown that this has resulted in the emergence of new cultural producers. It includes artists, musicians, photographers, poets, novelists, visual artists, comedians, film makers and entrepreneurs which is leading to unanticipated new configurations.

Other examples might include Sara Alfageeh’s attempt to recreate Marvel’s newest addition to X-Men; Dust, a female mutant from Afghanistan.

She was disappointed with how the character was sexualized and the lack of cultural awareness. Dust she pointed out, spoke Arabic, rather than Pashto for example and wore a skin-tight costume even though she was veiled.

This isn’t an apolitical or ambivalent development in Dr Hamid’s view. It is an active attempt to reconcile and adapt the religious tradition young Muslims have inherited, with their new technologically mediated, networked, cosmopolitan Western cultures.

They “are not only expressing themselves through art, but also challenging stereotypes and raising political consciousness”. Dr Hamid calls these new subcultures the “Muslim cool”.

These memes are part of this development believes Dr Hamid but they have an added pedagogical value.

This new medium for communicating details of religious law demonstrates the “social media savvy and power of online activity to bypass traditional authority structures and reach out to large audiences in unfiltered ways” says Dr Hamid.

Haroon viewed the development in a similar way, despite six tough years studying the details of Hanafi law at his seminary in Blackburn. “What we are observing is young educated Muslims taking the tradition seriously and engaging with it — bricoleurs!”

‘Bricoleur’ is a term re-purposed by Professor Ebrahim Moosa in his book, Ghazali and the Poetics of Imagination, to describe the way Ghazali and other imaginative people make new things from “quotidian objects” through a process of creative adaptation.

“The skill is making something so historically significant and complicated, accessible to an audience who otherwise do not know much about madhabs,” Haroon told me.

But this isn’t an attempt to replace authority structures for Zain, rather, it’s a method to augment and raise awareness of the importance of madhabs in the lives of Muslims.

“The madhabs are extremely vital for Islamic epistemology, and as for laymen and the vast majority of the community, it basically provides a framework for how to operate in your day to day life as a Muslim” he says.

“A madhab for someone at a basic level lessens the confusion and at bottom we are taught that these differences are a mercy”.

Haroon confirms this as he says Muslims are too busy in their day to day lives to confirm the Islamic validity of each and every act. These schools of jurisprudence allow Muslims to be “comfortable that their religion is well-thought through, coherent and systemized in a way that allows them remain connected to God while continuing with their lives” he said.

These differences Haroon continues, “show the beauty of the human mind, in that one can take so many meanings from a single source”.

“But the source is one”, he counsels with caution.

Muslims aren’t obligated to follow these schools of jurisprudence, as they emerged after the death of Prophet Muhammad. But Haroon explained that new challenges in Western societies are leading to intra-madhab introspection, as well as a more robust engagement with other madhabs.

“But given the dangers of interpreting scripture without a methodology, and the vast amount of conditions required for one to even to even consider themselves worthy of attempting to bypass tradition, it would be a folly to ignore the madhab — not to say extremely dangerous!”

These memes in his view are therefore more than welcome tools to educate people about madhabs and maintain their relevance to the general public.

Where are these new developments heading? Dr Hamid isn’t sure, as he thinks Western Muslim youth culture is a work in progress and hasn’t yet distilled and crystalized into clear and coherent cultural formations.

But “it will likely to continue to mirror and challenge dominant social media usage patterns and perhaps produce an artistic subculture of its own.”

A bricoleur, Professor Moosa says in another part of his book “demonstrates originality in the process of refinement and adaptation, making the borrowed artifact synthetically fit in with the new surroundings as if it had been there all the time and belonged there in the first place.”

Zain says people have jokingly encouraged him to make a “fiqh (jurisprudence) book out of memes”. Will memes someday “synthetically fit in with the new surroundings” becoming an educational tool to teach fine points of Islamic law?

Haroon laughs too. “Well, I doubt they’ll be used in madrassas, but as you can see they’ve had their impact”.

Originally published at www.onreligion.co.uk.